Torque

Torque is the measure of an objects tendency to rotate about a point. It is a measure of work, or the magnitude of a force acting through a distance. In reference to engine output, it describes the net twisting force produced at the crankshaft. The greater the torque output, the greater the twisting force. Torque about an axis can also be referred to as a moment, but this isn't typical nomenclature in engine discussions. When the term "engine load" is used, this refers to the percentage of maximum torque that is being produced by the engine.

It's important to understand that torque is not a time dependent variable. Imperial units of torque include inch pounds (in-lbs, lb-in) and foot pounds (ft-lbs, lb-ft, pound feet) while metric units of torque are typically given in Newton meters (N-m). Notice that these units include a force and a distance but no time variable. Additionally, there can be a torque about a point without any movement if the system is in an equilibrium state.

Power

Power is a measure of the rate at which work is performed or how much energy is consumed while a process is underway. Mechanical power is dependent on time and torque as it is the force generated through a distance per unit of time. Therefore, power identifies the total work done over a given time interval. In the U.S. we typically associate engine power in units of horsepower while kilowatts (kW) is a much more common unit of measure in other countries.

Horsepower is a fictitious concept based on the assumption that a horse can move a 33,000 pound object 1 foot every minute (33,000 lb-ft/min). Horsepower itself is not actually measurable by any instrument, it is calculated by measuring the torque at a particular angular velocity. In the case of reciprocating engines, this refers to the torque at an engine speed given in revolutions per minute (rpm) of the crankshaft. By measuring torque and rpm, horsepower is then calculated using the formula:

The constant 5,252 is derived from the fact that a unit circle 1 foot in diameter has a circumference of 6.2832 feet. Dividing 33,000 by 6.2832 equals 5,252 and resolves the units in the equation. Interestingly, but not coincidently, horsepower and torque curves will always cross paths at precisely 5,252 rpm.

Output Ratings

Engine performance for most vehicles is typically advertised by the peak rated engine power and torque output. These values represent maximum output - the highest power and torque the engine can produce and the rpm at which this occurs, respectively. In some applications, marine and agricultural, for example, engines may have additional ratings that represent there performance under partial loads, or the "continuous" rating versus the "peak".

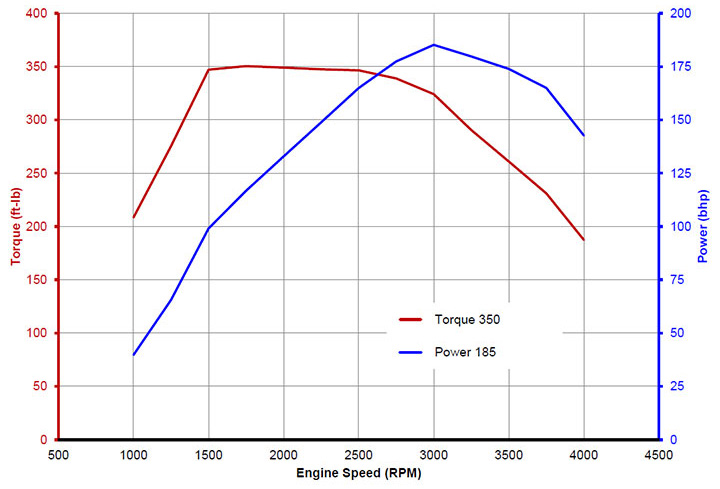

An engine will also reach peak torque before it reaches peak power because torque is produced independent of engine speed. Since power is the product of torque and rpm, it climbs more slowly than torque. Torque tends to plateau, followed by a steady drop at higher operating speeds due to rising frictional losses and diminished efficiency. Different factors control at what rpm peak torque is generated by an engine, especially with regard to airflow characteristics. Truck engines are typically designed to generate peak torque at low engine speeds at the sacrifice of high rpm power, but the opposite is true for many cars.

On a horsepower and torque curve, the power band is the engine speed range between the points where peak torque and power are produced. It represents the range where the engine will achieve the highest rate of acceleration. From figure 2 above, peak torque is produced at approximately 1,500 rpm and peak power occurs at roughly 3,000 rpm. The power band for this engine is therefore between 1,500 and 3,000 rpm. An engine's power band is an important aspect in selecting transmission and final drive gear ratios for a given application.

It is important to distinguish that a typical power and torque graph represents peak engine performance at wide open throttle and says very little about actual performance characteristics at partial loads. While the point of peak torque represents the engine speed where an engine is efficiently maximizing airflow, it is not practical to assume that the chart would be identical if measured at partial load.

Diesel Engines

Diesel engines often produce more than double the torque than they do horsepower. A major factor in this phenomena is that these engines are limited to lower engine speeds and there power band is limited by the rapid decline in torque at higher speeds. Turbocharged diesel engines are known for displaying relatively flat torque curves - that is, torque output peaks but remains very close to its peak value over a long rpm range. This characteristic is highly regarded in vehicles that are designed to tow because it is efficient in bringing heavy vehicles up to speed and maintaining speed on inclines when the engine load increases significantly.

With exception, small passenger car engines typically operate up to 4,000 rpm while pickup and medium duty trucks utilize engines that operate up to 3,500 rpm. Class 7 and 8 tractors employ engines that are generally limited to a maximum 1,900 to 2,100 rpm, but these trucks also rely on 10 to 18 speed transmissions with small steps between gears, which keeps the engine in its power band. Small marine applications also rely on engines in this speed range, but larger marine engines utilize low speed engines that operate at less than 1,000 rpm.

Gasoline Engines

Gasoline engines operate at higher engine speeds than diesel engines and thus the power and torque figures are generally closer to one another. Gasoline has a higher burn rate than diesel and thus these engines are more suitable for high speed operation. A typical engine will reach peak power between 4,500 and 5,500 rpm. Peak torque is also produced at much higher speeds, typically 3,500 to 4,500 rpm. Some gas engines designed for commercial vehicles exhibit lower peak operating speeds, but it is not common for a typical gas engine to reach peak torque before 3,000 rpm. Forced induction (supercharging or turbocharging) significantly flattens the torque curve because engine airflow is no longer dependent on the intake flow characteristics and restrictions.

Electric Motors

Electric motors are a special case in that they theoretically produce peak torque at zero rpm, peak torque is maintained through the entire operating range, and the power curve is perfectly linear. This is because power input to the motor is consistent and does not change with motor speed. In an internal combustion engine, power input is a product of the amount of air that is drawn into each cylinder, which changes with engine speed.

In practice, an electric motor produces peak torque at zero rpm and the torque curve remains flat until a point at which parasitic losses, in the form of friction and heat, transition from negligible to significant. From this point torque continues to fall off somewhat consistently, but the overall curve is extremely flat within a wide speed range.

Summary

We love high horsepower in our performance cars and big torque in our diesels because these terms represent the ability of each of these engines to perform their respective tasks. In reality, there is no reason to concentrate on one metric over the other, nor attempt to argue on the superiority of one over the other. Horsepower and torque are related measurements with separate clues into an engine's behavior - there is a reason that they are both provided, and not just one or the other.