There are many age-old myths used as the basis for arguments between inline and V configured engines. This article will not settle the backyard debate between I-6 and V-8 engine configurations nor will it determine that one has any competitive edge over the other. It will, however, explore distinct design benefits and limitations associated with the two very different architectures. The assumption that the arrangement of cylinders in any particular engine is an absolute definitive factor in performance characteristics is a simple fallacy. Designing (or selecting) an internal combustion engine requires careful consideration to packaging restraints, emissions, NVH, minimum power requirements, speed expectations, and fuel efficiency. Balancing these factors can be the tipping point between an inline and vee configuration.

Design Characteristics & Considerations

There is not a single defining feature that credibly categorizes or dictates the performance characteristics of an engine, although specific design attributes can affect certain behaviors. The design of an internal combustion engine is a complex process that must navigate strict criteria and constraints, including performance expectations, efficiency benchmarks, cost, and emissions. The engines we see before us today are the result of centuries worth of investment, research, and refinement driven by competition.

Comparing individual engine features in an objective manner is difficult in that it requires assuming that the remaining features are like-for-like. This makes it inherently difficult to compare inline and vee engines because of the many variables that ultimately contribute to performance and efficiency characteristics. A better approach might be to evaluate the constraints that are attributed with each design, respectively.

Displacement

Displacement is the single most important factor that directly correlates with maximum engine power and torque. Assuming there are no feasible improvements or pathways available - improving volumetric efficiency, parasitic loss reconciliation, increased engine boost, etc - to increase maximum power, an increase in displacement is the only solution. This does not mean that engine A is more powerful than engine B because it has a larger displacement; there are significantly more variables in play, and a practical engine is one that doesn't push its mechanical components just beneath their breaking point.

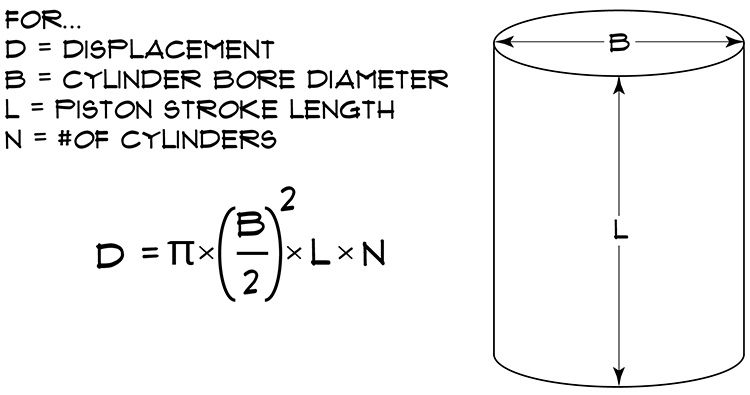

Displacement refers to the cumulative volume displaced by the pistons in all cylinders. It is calculated from the bore, stroke, and number of cylinders. As the piston travels from top center to bottom center, its two extreme positions, it forms a cylinder with a diameter equal to the cylinder bore and a length equal to the stroke length - the volume of this cylinder is equal to the displacement. The total engine displacement is then calculated by multiplying the single cylinder displacement by the number of cylinders.

Displacement is most often given in liters, cubic inches, or cubic centimeters. It increases proportionately with an increase in the cylinder bore diameter or the stroke length. The larger the displacement, the greater the volume of the air charge each cylinder can hold.

Manufacturers have to come to embrace small displacement turbocharged engines over large displacement naturally aspirated engines in modern times because they produce lower emissions and consume less fuel. Turbocharging significantly improves volumetric efficiency, thus they can be designed to produce the same (or more) power as a comparable naturally aspirated engine of much larger displacement. But, the lower displacement engine will consume less fuel and produce fewer emissions under light loads.

Bore-Stroke Ratio

The bore-stroke ratio of an engine is calculated by dividing the bore diameter by the stroke. The resulting ratio is unit-less, but describes these dimensions relative to one another. If the bore diameter is dimensionally larger than the stroke length, the ratio will be greater than 1. When the stroke length is dimensionally larger than the bore diameter, the ratio will be less than 1. Intuitively, when the bore and stroke dimensions are equal, the bore-stroke ratio is 1. Engines with a bore-stroke ratio greater than 1 are referred to as "oversquare", engines with ratios less than 1 are referred to as "undersquare", and engines with a 1 to 1 bore-stroke ratio are referred to as "square".

If displacement is to be preserved, then an engine designed with a short stroke must have a large bore and visa versa. Oversquare engines are widely common in racing applications that require operating at high engine speeds. Extreme examples include Formula 1 race cars, high revving motorcycles, and dirt bikes, which can have bore-stroke ratios in excess of 1.5.

Undersquare engines, those with a long stroke design, are much more prevalent in diesel engine designs. There are, however, always exceptions and this is only a generality. For smaller displacement engines, such as those found in pickup trucks and medium duty vehicles, a bore-stroke ratio between 0.85 and just below 1 are largely common. Larger engines utilized in class 7 and 8 tractors often have smaller bore-stroke ratios between 0.8 and 0.9.

| Model & Displacement | Type | B-S Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 6.6 liter Duramax | V-8 | 1.04 |

| 5.0 liter Cummins ISV | V-8 | 1.04 |

| 7.3 liter Power Stroke | V-8 | 0.98 |

| International DT466 | I-6 | 0.98 |

| 6.4 liter Power Stroke | V-8 | 0.94 |

| 3.0 liter Duramax | I-6 | 0.93 |

| 6.7 liter Power Stroke | V-8 | 0.92 |

| 14 liter Cummins N14 | I-6 | 0.92 |

| 6.0 liter Power Stroke | V-8 | 0.90 |

| 6.7 liter Cummins ISB | I-6 | 0.86 |

| 5.9 liter Cummins ISB, 6BT | I-6 | 0.85 |

| 9.3 liter Detroit 71 Series | V-8 | 0.85 |

| 14.9 liter Cummins ISX15 | I-6 | 0.81 |

| 12.9 liter PACCAR MX-13 | I-6 | 0.80 |

| 14 liter Detroit 60 Series | I-6 | 0.79 |

Performance Characteristics

Undersquare and oversquare engines often have different performance characteristics. The long stroke design is more typical in diesel engines, especially as displacement increases, because it encourages better low-end torque. As stroke length increases the crankshaft radius must increase proportionately. In fact, the crankshaft radius will always be equal to 1/2 the stroke length. A longer crankshaft radius results in a greater mechanical advantage produced by the connecting rod on the crankshaft. This effect is smaller than intuitively expected, however, because the angle of maximum fulcrum is achieved late in the combustion cycle when the cylinder pressure has been greatly diminished.

The consequence of a long stroke design is increased piston speed and acceleration, thus producing greater inertial forces as the mass of the piston and connecting rod move upwards and downwards in the cylinder. Considering that engine speed is a fixed property, i.e. one revolution of the crankshaft is the same action independent of the engine bore or stroke, the piston in an engine with a long stroke must travel a longer distance than the piston in of an engine with shorter stroke, but in the exact same amount of time. This is only possible because the piston in the long stroke engine is translating upwards/downwards in the cylinder at a higher rate of speed.

Oversquare engines exhibit the opposite behavior. An engine with a large bore and shorter stroke are suitable for high engine speeds and generally produce favorable high-end power at the expense of low-end torque. As the stroke length decreases, piston speeds are proportionately reduced and inertial forces remain within allowable limits at high RPM. Furthermore, a large bore engine design creates space for larger intake and exhaust valves, thus an oversquare engine can be designed to breath efficiently at high speed.

Because diesel engines are already limited in speed we don't often see largely oversquare examples, but a near square ratio is somewhat common in cars and pickup trucks.

Engine Speed Limitations in Diesel Engines

Traditionally, diesel engines are not designed to operate at high speeds. Some high speed examples exist in the passenger car category (4,000 to 4,500 rpm max), but this remains significantly lower than modern gasoline engines that can reach 6,000 rpm or more. In the light-heavy duty truck segment, engines are typically limited to engine speeds less than 3,500 rpm. As the engines get physically larger, maximum engine speeds get lower; class 8 tractor engines typically operate at maximum speeds in the 1,900 to 2,200 rpm range.

Application criteria plays a critical role in these operating speed ranges. A small car is expected to have certain acceleration and performance characteristics that is widely different than the expectations of a heavy duty pickup truck. Likewise, fuel efficiency is a top priority in semi-truck engines and therefore they are designed to operate within a narrow speed range. These trucks utilize transmissions with up to 18 gears that take only a small step with each shift, keeping the engine in an RPM range that maximizes torque and efficiency.

The greatest factor that limits the maximum engine speed in diesel engines is, however, the fuel burn rate. Diesel fuel must be injected into the compressed air charge, diffuse in the air charge, reach the autoignition temperature, and then ignite after a short delay. This delay is extremely short and is minimized by using high cetane fuels, but ignition does not occur as quickly as it does in a spark ignition engine and diesel fuel exhibits a longer burn profile (duration) than gasoline.

Combustion, cylinder evacuation, and the "reloading" of the air charge occurs very rapidly in an internal combustion engine. As engine speed increases, the events in each stroke must happen proportionately faster. A diesel engine therefore reaches a maximum speed at which fuel cannot be diffused fast enough for an efficient combustion event to occur. If combustion occurs late in the power stroke, less energy is extracted from the charge and much of it is wasted through the exhaust manifold.

Engine Balance

Inline 6 and V-8 engines are balanced on both the first and second order. This indicates that primary and secondary inertial forces counteract and result in a net force of zero. The reciprocating masses in cross-plane V-8 engines produce a rocking moment at the crankshaft because although the inertial forces are equal they are produced in opposite directions due to the 90 degree angle between connecting rods on opposite banks. This rocking moment produces a vibration along the long axis of the crankshaft that must be countered.

Inline 6 engines are often described as "perfectly" balanced because they do not produce this same rocking moment. This configuration is also noteworthy for the resulting smooth power delivery. Engine balance is a critical design consideration because unwanted vibrations can excite and amplify through the vehicle, causing undesirable NVH. Crankshaft dampers and counterweights formed into the crankshaft are used to balance engines and mitigate vibrations.

Emissions

In modern times, tailpipe emissions are a critical element of diesel engine design and may very well be the most challenging detail to overcome. Manufacturers do not have the luxury of ignoring emissions related laws and regulations. In fact, there have been major lawsuits against most domestic manufacturers that allege "emissions cheating" with "defeat devices". Significant punitive damages are generally collected in these cases and some have even resulted in expensive recalls. Whether there were intentionally evasive acts of malice in these instances or not, it proves that manufacturers are constantly under the microscope.

Emissions are not a product of engine architecture. Airflow characteristics, fuel mapping, and engine timing are primary considerations in controlling and reducing emissions. Furthermore, modern aftertreatment equipment, specifically for diesel engines, is extremely efficient in converting the exhaust constituents post-combustion. The adoption of these technologies has thus granted some leniency in engine calibration as the exhaust is "cleaned" as it travels through the system.

Inline 6 Engines

Inline 6 cylinder engines are generally found in medium to heavy duty trucks, agricultural equipment, marine, and industrial machinery. There is not necessarily a generality that this engine orientation is the best or only choice for such applications. Historically, a wide variety of engine formats have been used across a diverse range of applications. However, a significant benefit of the inline 6 design, from a manufacturers perspective, is the scalability resulting from the inherent balance these engines display.

In the pickup segment, the Ram HD (formerly Dodge Ram models) employs an inline six cylinder engine in a segment that has largely been dominated by V-8 engines. More recently, GM introduced a 3.0 liter inline six diesel engine for its Silverado and Sierra 1500 models. This is both the first and only such engine in its class.

Inline 6 engines are typically undersquare with a small cylinder bore relative to a long stroke length. A significant factor in this characteristic is that inline engines are relatively long - significantly longer when compared to a vee engine of the same displacement and number of cylinders. Naturally, as the bore diameter increases so must the overall length of the engine. Utilizing a long stroke length is therefore necessary in preserving total engine displacement while minimizing physical length.

Because of their length inline engines may experience higher torsional stresses on the crankshaft. Thus, inline engines tend to have a relatively heavy crankshaft. While the additional weight could tip into the negative category, a massive crankshaft has a flywheel effect that provides torque in the form of momentum. This low-end or even off-idle torque is useful during initial clutch engagement in that the engine will be less likely to stall because of the kinetic energy provided by the rotating mass. While this effect is present in all engines, the more massive crankshaft in inline engines may provide a marginal, but additional advantage.

Inline engines are often thought to be more easily serviced than vee engines because there are smaller spacial restraints to the left and right of the engine. While this is not a universal truth, the serviceability factor is important in many industries where engines are expected to undergo overhauls in place, i.e. without pulling the engine from the vehicle or machine.

Primary Advantages

- Dimensionally narrower, greater accessibility to the sides of an engine

- Engine in "perfect" balance

- Smooth power delivery

- Scalability

Disadvantages

- Limited operating speed

- Greater torsional stresses applied to the crankshaft

- Maximum bore size limited by engine length

V-8 Engines

V-8 engines are arguably one of the most versatile and common high displacement engine configurations in existence. It has historically dominated the consumer automobile market in large cars, SUVs, and pickup trucks. In the diesel pickup category, it has been the configuration of choice for GM since 1978 and Ford Motor Company since 1983. V-8 diesel engines are also prevalent in the medium duty truck segment, but have not been the engine-of-choice in the heavy duty industry for some years now. They remain popular in the marine industry, but I would suggest that inline engines are equally common and this is a difficult market to gauge due to widely varying vessel sizes.

V-8 engines are dimensionally compact and thus more square than rectangular. They therefore are more likely to require less length at the expense of a greater width. V-8 engines generally have a more-square bore-stroke ratio than inline engines. Modern examples in the pickup truck category range from 0.90 to 1.04. The shorter stroke length contributes to strong mid-range performance, but this can come at the expense of low-end, part-load torque.

Lower torsional forces on the crankshaft (due to its shorter length) and shorter stroke lengths contribute to relatively high maximum engine speeds for some V-8 models. Serviceability is generally acceptable for these engines, but the lack of access to the left and right of the cylinder heads can make accessing the valve covers more difficult. Furthermore, turbochargers are generally located in the valley where they can be difficult to maneuver on and off the engine.

Primary Advantages

- Dimensionally compact

- Lower torsional forces applied at the crankshaft

- High operating speed

Disadvantages

- Inherent primary and secondary balance (cross-plane only), but rocking moment produced at crankshaft

- Engine width may interfere with access to and/or below the cylinder heads

Conclusion

Peak horsepower and torque figures can actually be quite irrelevant in that they completely disregard part-load characteristics. An engine may produce excellent horsepower and torque at full load but respond sluggishly under lighter accelerator inputs. There may thus be an expectation that a higher performing engine has favorable throttle response and strong power across the board. Unfortunately, more-comprehensive performance mapping is not part of the experience and we, as consumers, tend to get carried away by those peak horsepower and torque numbers.

Even so, it's quite futile to base an argument in favor of a particular engine entirely on its architecture. Take the recent (and now cooling) battle between the 6.7 liter Cummins I-6 and the 6.7 liter Power Stroke V-8 engines; two extraordinarily capable machines of the same nominal displacement, similar peak performance attributes, but of two distinctly different designs. And as a final thought, drivetrain configuration has become an increasingly important, dare I say pivotal aspect in overall performance characteristics.